Health and wellbeing in refugee camps

Poor and hungry orphan boy in a refugee camp. Photographer: Magsi (Shutterstock, 2020).

The deathly impact of the burden of hope - a comparative analysis of health and wellbeing conditions in refugee camps

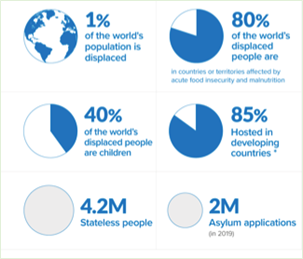

Title: Data representing the migration crisis, Source: UNHCR, 2020

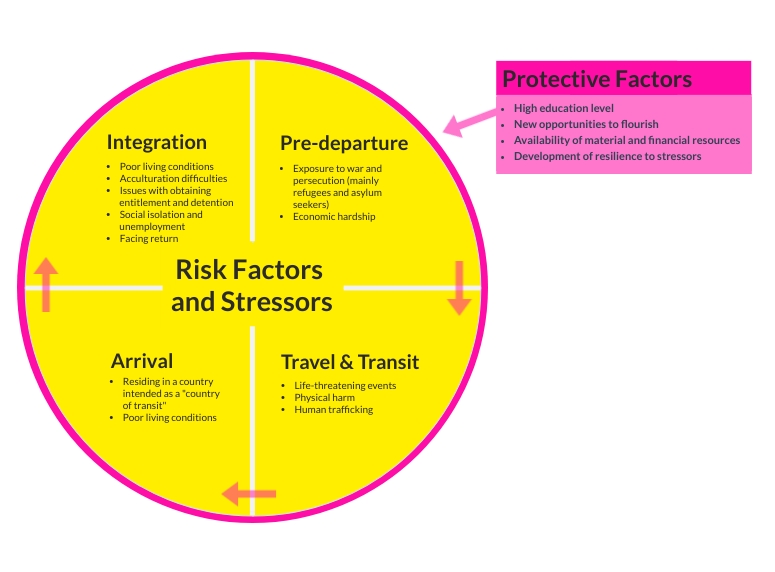

Mental health difficulties are also prominent in refugee camps as shelter inadequacy results in high levels of psychological stress. On average, in refugee camps worldwide, the prevalence rate of PTSD is 30.6% and for depression, it is 30.8% (Posselt et al, 2018). Comparatively, only 3.4% of the world’s population has depression (Ritchie, Roser, 2018). The causes of these mental health stressors are predominantly forced separation from family, loss of family/friends, loss of status and home, witnessing or suffering from physical or sexual violence. This state of limbo has also been proven to aggravate pre-existing vulnerabilities that occurred from pre-migration trauma, including living in a war zone. The longer the displacement, the more likely it is to decrease resilience. There are three themes that promote wellbeing: socio-cultural and religious opportunities, a future or goal orientated mindset and finding a purpose in life despite everything else. Examples of these are respectively social support, education or employment and activism. These findings are consistent in dissimilar camps in multiple countries with people of different cultural needs. Normality is created through internal, identity development functions. Another buffer against psychological distress is social connectedness, such as having a sense of belonging and self-accomplishment with others (Posselt et al, 2018).

To formalize these concepts with concrete examples, a comparative analysis will be conducted on multiple refugee camps

and how well they have assimilated these identity development functions.

Kilis camp, a shelter in Turkey primarily with Syrian civilians, is notorious for having been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 2016. Whilst nominating the camps itself for the prize, Ayhan Sefer Ustun, deputy head of the Justice and Development Party at the time, states “[Turkish] people share their jobs, houses, trades and social spaces” with Syrian refugees. Opened in 2012, the camp consists of 2,053 identical containers with satellite dishes, streetlights, fire hydrants, workers on hand to fix plumbing and electrical issues, metal detectors and x-ray machines upon entry alongside fingerprint identification. Hasan Kara, mayor of Kilis in 2016 believes the camp should become a worldwide example for human rights protection (Lee, 2016). This camp, ran by Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency ensured hygiene, connectedness and safety were at the forefront of the blueprints. The available education, employment, and community feeling doubtlessly contribute to enhancing the wellbeing of the inhabitants. Children even have access to psychological support (McCelland, 2014).

Sarah Marine Surget

Categories

Categories, Health, Highlighted, Human rights, Refugee camps, Refugees, Statistics